Artists

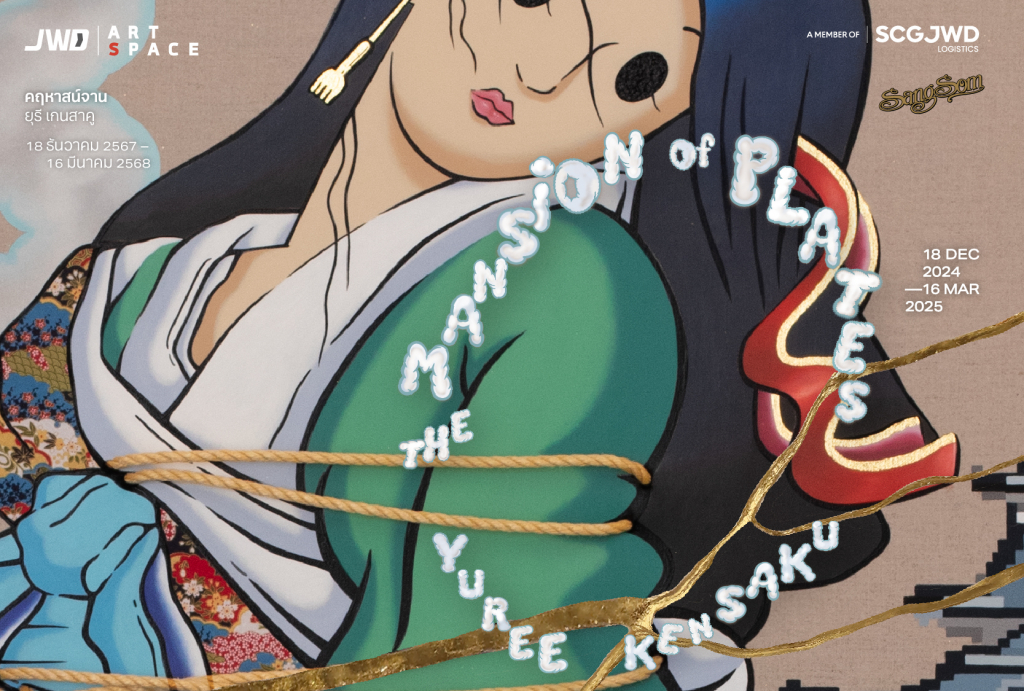

Yuree Kensaku

Date / Time

18 December 2024 – 16 March 2025

10 AM - 7PM

Location

JWD Art Space

About

About

Unveiling Resilience: Yuree Kensaku’s New Body of Work

By Miwako Tezuka

Yuree Kensaku’s latest paintings dive deeply into the collective struggles and resilience of women, drawing from an array of cultural stories and archetypes. While her vibrantly colored anime-like sensibility remains intact, inviting viewers into each piece, in her new body of work, this new body of work examines how myths, histories, folklore, popular culture, and urban legends represent women and also stereotypes them. Characters such as ghosts, monsters, and antiheroes feature prominently, yet they are rarely straightforward villains. Instead, Kensaku approaches these figures with a nuanced eye, casting them as contemporary allegories in her signature pop style, mirroring the complex psychology of our social, political, and cultural lives.

Her main subjects are tragically iconic women across history, place, and the imaginary; for example, Okiku from a classic Japanese horror story, Medusa from Greek mythology, Mae Nak Phra Khanong of Thai folklore, as well as the witches persecuted in medieval and early modern Europe and colonial Massachusetts in North America. There are, however, some exceptions, mostly from the contemporary period like Lisa from Blackpink and the fierce girls of Sailor Moon, who serve as icons of empowerment. This diverse cast reflects Kensaku’s broad research into the impact of storytelling and the controlling voice of the narrator, shaping archetypes that inhabit the human consciousness across generations. And while such mythologization can be reductive, reinforcing the often rigid nature of stereotypes, the artist subverts this effect, transforming these figures into revelatory characters embedded with lasting social critiques by virtue of never completely disappearing. In essence, Kensaku’s exploration in her new body of work lies in the biases woven through these stories—biases that continue to influence how women are seen today.

Accidental Femme Fatale

The figure of the femme fatale is one of the most enduring female archetypes, especially since the French fin de siècle art and literature made her presence so iconic. Often seen as both seductress and destroyer, she famously appears in works like Charles Baudelaire’s Les Fleurs du Mal, embodying a duality of beauty and danger that has fascinated and haunted artists for centuries. In many of Kensaku’s paintings, female protagonists renowned for their beauty become a sort of accidental femme fatale, initially victimized or betrayed but ultimately returning as powerful, vengeful figures.

Take, for example, the case of Okiku. The titular character from one of the most popular horror stories in Japan, Banshū Sarayashiki (The Mansion of Plates), is bound and surrounded by a haunting swirl of smoke-like numbers, one through nine. Although there exist numerous versions, the general storyline is set during the medieval period and tells of Okiku, a young maid serving a high-ranking samurai in the fiefdom where Himeji Castle still stands today (in Hyōgo Prefecture). Her primary duty was to care for a set of ten porcelain plates, an important family heirloom of the regional lord. Known for her beauty, Okiku attracted the samurai’s attention, and when she rejected his unwanted advances, he became enraged by her refusal and lack of obedience. He hid one of the plates and accused her of neglecting her duties. In feudal society, such a mistake was fatal. Okiku was hanged from a pine tree, and her body was thrown into a well within the castle precinct. Since then, her ghostly voice has been heard at night counting to nine and crying out in the end, “the tenth is missing!” Those who linger to hear her final cry are said to meet death at her hands.

Kensaku depicts Okiku’s ghost emerging on the grounds of Himeji Castle. Behind her is the storied well marking her tragic end. Indeed, this so-called “Okiku’s Well” has become a contemporary tourist attraction where visitors gather to imagine her sorrowful tale. In the painting, she is surrounded by wisps of smoke or clouds shaped into numbers one through nine. Nine floating saucers in an 8-bit style also hover around her, reminiscent of the collectible points in a video game. It seems she is not only bound by the rope but also trapped in an endless loop of challenging stages of the game. In the life of a woman, the final, tenth stage might be an unattainable level. By turning Okiku into an icon of this struggle, Kensaku’s painting highlights the underlying structure of recurring narratives: women gaining recognition only after death or through transgression. In Kensaku’s contemporary reinterpretation, Okiku becomes a lasting reminder of the dangers women face when defying societal expectations, particularly the demands of male desire.

“Common Differences”

A notable stylistic development in Kensaku’s recent work is her blending of painterly realism into her signature pop aesthetic. While her past work drew from the visual language of comics and animation, the artist now demonstrates a renewed interest in a painterly approach that pays close attention to textural details rather than flattening them. This shift becomes especially apparent when her subjects are of Western origin, and the distinction signifies the differing socio-cultural contexts she references while revealing a similar structure of violence against women across cultures.

For example, a witch standing at the stake on fire is depicted as a black cat in a black dress with a pointed hat, like a Halloween costume ensemble of Hello Kitty gone dark. The subject derives from the historical witch hunts. A disembodied hand enters the scene from the left, holding up a crucifix to ward off “evil” which meant anyone (majority women) deemed “different” by the dogmatic Christian authorities in Europe from medieval to early modern times, as well as in colonial America. Here, Kensaku foregrounds the universal tendency to scapegoat women, with reasons that could be manufactured from anything ranging from expressing sexual agency to simply having an independent mind. In short, while the artist uses contrasting styles to acknowledge social, cultural, and religious differences between East and West, her new body of work underscores a shared history of gendered struggles and exposes the “common differences” that span geographic and cultural lines.[1]

The One Who Holds the Figure Ten

Yuree Kensaku has made it clear that she does not consider herself a “feminist” artist. Some of the issues underlying her work today do align with feminist concerns; however, this alignment appears to have formed organically rather than as a consciously adoption of feminism. Her art has always been deeply personal, transforming her fears and phobias into characters in a chaotic, imagined universe. At this stage of her life as a woman, her self-reflection has led her to question the root causes of some of her fears: why women—and for that matter, also gender minorities—are often the victims in many stories. It seems as though, to survive the series of escalating challenges in life, women must ultimately attain supernatural power, much like in a role-playing game.

In this sense, her depictions of the supernatural creature Kyūbi no kitsune (the nine-tailed fox) are particularly captivating. Although the legend of this shapeshifting beast originates in China, the nine-tailed fox has been adopted into the pantheon of yōkai—monsters and spirits in Japanese folklore that are conjured up to explain mysterious phenomena and often reflect societal anxieties. As a symbol associated with cunning and beauty, the nine-tailed fox appeared first in folklore as the beautiful lady Tamamo-no-Mae during the reign of Emperor Toba in the early twelfth century. When the emperor became intimate with her, he began to fall ill. When an onmyōji, a Japanized Taoist shaman and court advisor figured out that she was not a human but the nine-tailed fox, he used his divinatory powers to imprison her in a large rock. The beast was no longer a threat to the emperor, but the stone itself became poisonous to those who came too close, earning it the name Sesshō-seki (killing stone).

This onmyōji is portrayed prominently in Kensaku’s composition as an anthropomorphized wolf. [image] The work is packed full of symbols, and deciphering them connects it to many other pieces Kensaku produced for this exhibition. A remnant of the tamed monster—a head of a pink fox with a red bow—peeks out from the background behind him. His sources of power, i.e., the five elements (metal, earth, water, fire, and wood), fill the space around him. In addition to his monster-subduing abilities, he is said to be able to predict the gender of newborns; indeed, a stork is shown delivering a baby in a sack, which appears pixelated, as if not yet fully loaded into the game of life as a gendered being. And unmistakably, the figure ten, that elusive final count that Okiku is never able to reach, appears in the top right, reminding us of the eternal loop of challenges and struggles.

The contrast between the wolf’s menacing expression and the benign countenance of the fox in this painting reflects the artist’s observation of the gendered world order—overpowering male energy versus subjugated female presence. Perhaps the onmyōji in Kensaku’s representation is not a hero, as he is frequently depicted in folklore, but an allegory for the unseen “narrator” of those tales, often a male voice that controls and constructs a culture advantageous to him. This is the structure of hegemony: a “particular social and political order” that “culturally saturates a society so profoundly that its regime is lived by its populations simply as ‘common sense’.” As Griselda Pollock observed, such “common sense” infiltrates society, embedding certain biases that continue to shape how we perceive female archetypes.[2]

Resilience Beyond Stereotypes

The motif of the nine-tailed fox reappears in other works within Kensaku’s series. By incorporating this mythical creature as a recurring symbol, Kensaku highlights how deeply ingrained this character is even in our contemporary imagination. In 2022, the “killing stone,” which allegedly still exists in Nikko National Park, made headline news when it split into two, leading to sensational reports that “[A]n evil fox spirit is on the loose after breaking free from her rock prison”.[3] Kensaku takes a cue from this news and reimagines the now world-famous fox spirit as contemporary characters that seem to have found ways to weave new narratives.

One of the paintings depicts the rock splitting in half with a bang. The pink fox with the red bow, its tails swinging around, looks alive and ready to sprint. In the foreground is the yuru-kyara (literally ‘soft character,’ meaning a mascot) named Kyūbie, playing a drum as if to announce the resurrection of the fox spirit after 900 years of imprisonment. Although the nine-tailed fox is literally Kyūbie’s spirit animal, its design was developed by the Tochigi Prefectural Government to attract tourists by capitalizing on the region’s legend. Naturally, the focus has shifted from the negative, monstrous image to one that is cute and cuddly. Beyond this officially sanctioned transformation, the question of what the nine-tailed fox would do after the spell was broken is left to the viewer’s imagination. Kensaku’s own vision for the freed fox spirit’s destiny is seductively presented in another painting, situated in the context of contemporary popular culture. In this work, Lisa from Blackpink stands on the illuminated stage, pushing aside a curtain of chains and presenting herself as a confident embodiment of female beauty. In her left hand, she holds the fox mask that she no longer wears, while fox ears and a tail are now unapologetically part of her identity.

Conclusion

Kensaku’s latest series prompts us to reconsider the myths we live by and to recognize the enduring spirit in stories that refuse to be forgotten. Through complex imagery inspired by a variety of sources, she encourages her audience to question the structures that define female roles in myth, art, and society. Her art not only critiques the historical stereotypes of femininity but also reclaims these narratives, showing how strength is born from struggle. As a series, these works capture the mutability of identity, showing women as multifaceted beings, simultaneously embodying vulnerability and resilience.

[1] Chandra Talpade Mohanty’s discourse on “common differences,” as referenced by Maura Reilly in her “Introduction: Toward Transnational Feminism,” in the exhibition catalogue Global Feminisms: New Directions in Contemporary Art (London; New York: Merrell, 2007), pp. 14–45. The Global Feminisms exhibition, co-curated by Maura Reilly and Linda Nochlin in 2007 (toured to Davis Museum, Wellesley College, MA, and the Brooklyn Museum, NY), redressed the universalist problem of Western feminist frameworks by building on Mohanty’s concept of “common differences,” which acknowledges the shared as well as unique struggles of women across diverse cultural, social, and economic contexts.

[2] Griselda Pollock, Differencing the Canon: Feminist Desire and the Writing of Art Histories (London and New York: Routledge, 1999), p. 10.

[3] Megan Marples, “A Japanese ‘killing stone,’ said to contain an evil 9-tailed fox spirit, has split in two,” CNN, April 1, 2022, https://edition.cnn.com/2022/03/31/world/japanese-killing-stone-spirit-scn/index.html [last accessed on October 28, 2024].

Press release

Press release

Artist

- Yuree Kensaku

Work

Work

Related Exhibitions

Related Exhibitions

Downtime Parlor

Downtime Parlor looks at the aftermath of political intensity not as a rupture b...

WHERE WE ARE LANDING

JWD Art Space is pleased to present Where Are We Landing, a group exhibition tha...

Modern Eden: Boys’ Garden / Girls’ Sanctuary

JWD Art Space is pleased to present Modern Eden, an exhibition by Anmom and Phai...

The Dark Rainbow Wave

‘The Dark Rainbow Wave’ is a phrase that represents the mixture of feelings—capt...

AMINIMAL | Working Between the Lines

AMINIMAL | Working Between the Lines, the exhibition features Mit Jai Inn, Andre...

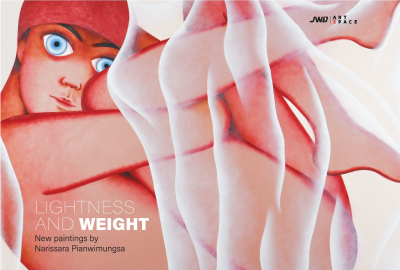

Lightness and Weight

Dreams and imagination are like balloons filled with gas, floating freely in the...

My Cart

My Cart