8 Contemporary Artists Reimagining the Still Life

You may have seen the painting that combines things together in one frame. Vase, flowers, fruits, plate, costumes or other stuffs, which have compositioned by lighting, colors, position. That is the type of Still Life Model since 15 Century. This kind of composition may look easy in some people’vision, but have you ever know that it reflects to the character and taste of the artist, or even attitude. Mostly, those paintings have the looks of luxury or wealthness, bu that was the beauty according to the values of an old age. And the world has changed, we live in the world that Digitals connects knowledges together; taste, technology, creativity, fashion music, food, etc. These are effects to human perception, and showing through the contemporary ways of life. Even the Still Life in the old form has adapted.

JWD Art Space selected 8 artists who explore the material world through abstract painting, performance, craft, and digital media. They document what it’s like to live, consume, and simply make art today.

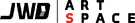

Anna Valdez

She draws and paints tables and floors crowded with art books (featuring David Hockney, Georges Braque, and Philip Pearlstein), plants, cow skulls (clear nods to Georgia O’Keeffe), conch shells, and decorative vases evocative of ceramic traditions from around the world.

“My subjects might look like compilations of ordinary mundane objects, but together they tell my specific story of painting investigation through art lineage, symbolism, and composition,” said Valdez. In this way, her still lifes become skewed self-portraits.

Valdez noted her interest in the Dutch vanitas tradition of painting from the 17th century, in which artists painted symbols of death to remind viewers of their own mortality. “By incorporating plants, shells, bones, and stones, along with paintings, sketches, ceramic objects, and fabrics, I am referring to the natural world, time, and contemporary life,” said Valdez. In early November, Denver’s David B. Smith Gallery will exhibit new, large-scale still lifes by the artist based on installations she’s created in her studio.

Arden Surdam

Arden Surdam’s photographs embrace the macabre. They feature sausage links trailing down a giant plastic tarp, bloodied animals, and stained sheets. It’s no surprise that she cites Francis Bacon, master of the grotesque, as a major influence. Recently, she’s been thinking about the artist’s diptychs and triptychs, especially Study from the Human Body (1983). It looks, she said, like “a slippery human chicken.” Bacon’s multiple-canvas works—which both suggest and evade narrative, linear readings—were themselves informed by the photography of Eadweard Muybridge, who famously shot animals’ movements in serial frames.

Recently, Surdam has been playing with similarly sequenced still lifes, asking viewers to look at four pictures of varying perspectives on the same few objects (a photograph, a glass surface, and a shiny, cream-colored sheet, for example) to extrapolate a larger scene and narrative. Surdam is now previewing her first monograph, Glut, and will have work in Phaidon’s forthcoming book The Kitchen Studio: Culinary Creations of Artists.

Daniel Gordon

To make his still lifes, Daniel Gordon takes photographs of everyday objects from the internet—fruits, vases, flowers, pitchers—then reassembles them in his studio and photographs the final compositions. The resulting frames are vibrant and complex: Looking at the two-dimensional pictures, the viewer must distinguish between real and digital space. Misshapen apples can be blue or purple, while onions look simultaneously flat and like collaged, three-dimensional objects.

A tricky sense of unreality and distortion creates intrigue across Gordon’s series. “My work has engaged with genres of still life, portraiture, and landscape,” said the artist. “I like to work within a genre so I can hopefully add to a tradition and play with some of the established conventions.” Through lockdown, Gordon has made smaller still lifes that incorporate real household items into his compositions. He calls them “Night Pictures,” since he’s only been able to work on them in the evenings.

Hilary Pecis

Her vibrant still lifes are filled with art-historical references, and with art itself.

The still life offers Pecis the ability to reference artists, living and dead, who are working (or have worked) in very different modes. “I find that there is a lot of freedom within the parameters of the still life,” she said. “It is a place to start, but there are infinite possibilities.” She cites the “color and application” of the Fauvist movement and California Funk artists as major inspirations. This November, she’ll exhibit her still lifes and landscapes in a solo show at Spurs Gallery in Beijing.

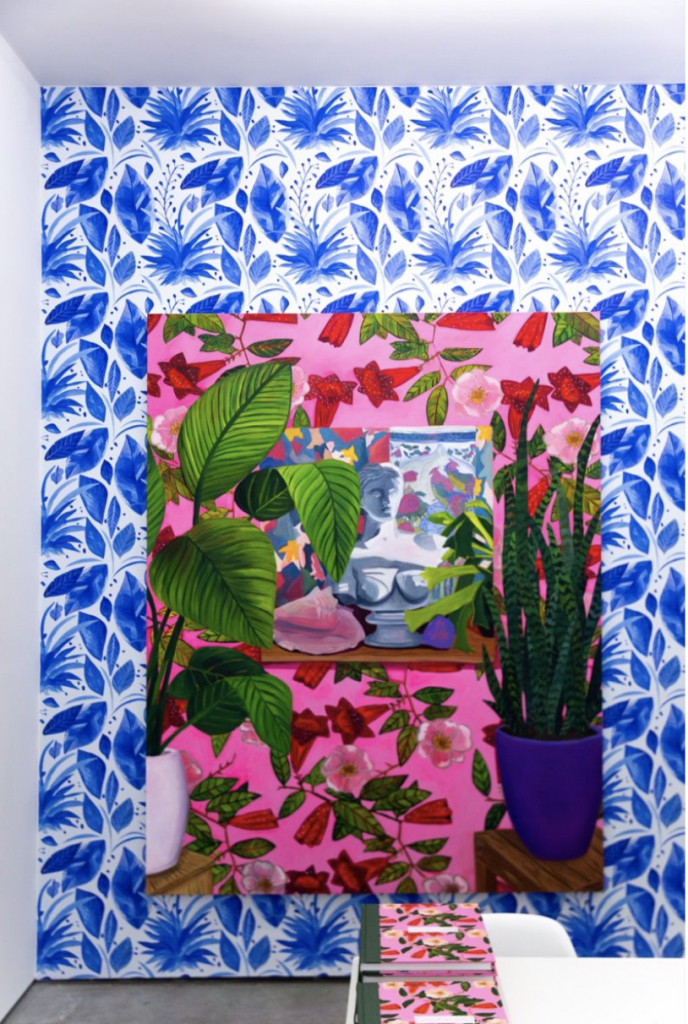

Holly Coulis

The appeal of painting still lifes is in stillness itself. “In other genres (even abstraction), there is paused movement,” she said. “A still life was still before it was painted, and after. Until someone or something comes to rearrange or to disturb it.” Such compositions feel “intimate and personal” to her. Looking at Coulis’s still lifes, a viewer is gazing at an unseen character’s private things. Solidly colored lemons, vases, cigarettes, knives, and cats dance around Coulis’s canvases, cheerfully bumping against one another. The artist outlines her forms many times in varied, bold hues, giving them radiant, vibrational auras. Pop art, Cubism, and abstraction inform the flat color, geometry, “off perspective,” and playfulness in Coulis’s paintings.

Coulis said that right now in her studio, she’s thinking about how to shift the lines in her paintings and “find a way to make them move more.” She’s also experimenting with making her paintings more abstract, pushing them to the very edge of what she calls “still life–ness.”

John Shin

John Shin

He believes that still lifes offer viewers the chance to appreciate the beauty of everyday objects. The form, she said, presents a “preserved and memorialized” reality that depicts the artist’s “systems, culture, and history.” Shin, who is known for her often monumental installations, has mounted dozens of sports trophies atop a long, white plinth; built structures composed entirely of discarded lottery tickets; and made an outdoor sculpture with broken umbrellas.

“I’m interested in engaging participants and communities in the process of collecting large quantities of everyday objects and detritus,” said Shin.

“I transform these materials to be in dialogue with larger social concerns and in response to the site’s context.” She recently completed a large-scale installation, Floating MAiZE (2020), for the Winter Garden Atrium at Brookfield Place in New York City. The work repurposes more than 7,000 green Mountain Dew bottles into a sculpture that resembles a faux cornfield. Shin said she wants to connect the “harmful consequences of industrial scale agriculture of corn to the unhealthy consumption of high fructose corn syrup in processed foods and beverages,” and lead viewers to consider how food production, nutrition, and pollution are intertwined.

Nicole Dyer

She updates the grand Pop art tradition of incorporating representations of branded foodstuffs into her art, à la Andy Warhol and, more recently, Katherine Bernhardt. She’s made floor sculptures of La Croix and Vintage-brand seltzer cases, and a multimedia painting with a Quaker Oats package at its center. Faux candy conversation hearts, ginger chews, and Froot Loops adorn the borders of her highly textured works. Dyer is interested in how products can “trigger an intense emotional response” in a viewer, such as nostalgia, hope, or commitment. Consumerism is a major concern for the artist—her work considers how seltzer brands accrue cult followings and how “colorful, matte packaging can make junk food appear healthier.”

While Pop art is ostensibly her most direct influence, Dyer is also inspired by a much older aesthetic tradition—Dutch still-life paintings of food. “I love the compositions, detail, and dramatic lighting,” she said. “I’m interested in the effect of similar compositions but made up of modern products and brighter colors.”

Pedro Pedro

A curious, surrealistic physics infuses Pedro Pedro’s still lifes. Socks, a banana peel, shoes, and a hat appear to droop like Dalí clocks. The chair cushions and tables that hold them are slanted so vertically that it’s amazing all these objects haven’t slipped off. Appropriately, Pedro said he’s drawn to the still-life form for its “banality and mystery”—in his paintings, the everyday becomes deeply, compellingly weird. Pedro said that the color and vibrancy of Colombian artist Fernando Botero’s still lifes inspire him, as well as the “movement and detail” in the work of Italian Baroque painter Giovanna Garzoni. While he also looks back to Impressionist and Post-Impressionist compositions, the artist added that he’s not attempting to “break or honor” any specific traditions—he simply likes to “sample” elements from other paintings. At the moment, he’s working on a composition of tomatoes on a vine that references a grocery store advertisement he recently received in the mail.

Stephanie H, Shih

She makes ceramics that resemble foods found in East Asian grocery stores—Kikkoman soy sauce, Sriracha, and Botan Calrose rice, for example. “My work is about shared nostalgia,” said Shih. “I like creating vignettes that are ambiguous enough to speak to a large swath of the Asian American diaspora while also being specific enough to speak to distinct memories.” Shih’s three-dimensional objects stimulate viewers’ desire, inviting them to imagine touching the works and feeling their weight.

The sculptural aspect draws Shih’s audience into her exhibition spaces “both physically and psychologically.” Starting on August 17th, a Perrotin viewing salon will exhibit a portion of Shih’s newest series which, in sum, features 30 ceramic soy sauce bottles from across the Asian American diaspora.

Latest Articles

Latest Articles

Preserve Your Art Professionally

From the moment you buy an artwork, its countdown begins. As you store your art ...

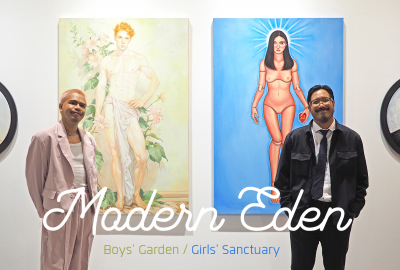

Modern Eden

“Actually you are a monkey, and love has no gender.” This is one of ...

Art Logistics Services and Sustainability Trends

The trend of environmental sustainability has been around for quite some time no...

The Value of Art Insurance

Art insurance is not just for collectors, or institute, but it is also a strateg...

My Cart

My Cart